My project is on version 2.3.4, and I have implemented a critical fix. What is the next version number? It it 2.3.5 or 2.4.0? What should I write into the commit message? Do I need to add an entry to the changelog? In this post, we will discuss some established conventions and automation of versioning in software development.

Semantic Versioning

A widely adopted system for versioning software is Semantic Versioning, or SemVer1 for short. Chances are high that you have seen or used it already, perhaps even without realizing that this intuitive system is actually a strict specification. SemVer versions may look like 2.10.4, 0.2.0 or 1.2.1-rc.2.

A SemVer version is a <major>.<minor>.<patch> string, where major, minor and patch are numbers starting with 0 and incremented in steps of 1. In short, the new version after a code change is determined by the following rules:

- After a breaking change,

majoris incremented:1.2.3->2.0.0 - After a non-breaking change or new feature,

minoris incremented:1.2.3->1.3.0 - After a fix,

patchis incremented:1.2.3->1.2.4

When major is incremented, minor and patch are reset to 0. When minor is incremented, patch is reset to 0. Some additional rules include:

- Versions are compared piecewise:

2.3.4>2.2.5>2.2.4>1.4.5 - While the version is

0.X.Y, anything may change or break at any time.1.0.0is the first stable release, and only then do version increments follow SemVer. - There may be pre-release versions, for instance

1.2.3-alpha - There may be build metadata, for instance

1.2.3+sha23h324ee9

For more details and formal definitions of the rules, as well as a handy FAQ, consult the official specification at semver.org.

While this specification is neat and not overly complicated, one might wonder how much (mental) work is needed every time a new version of the software is released. Do I need to go through all code changes from the last few weeks to try and recalculate the upcoming version?

Conventional Commits

The answer is “no”, at least if we are using version control (git). Conventional Commits2 is another specificiation closely related to SemVer, dictating the format and content of commit messages. By following the Conventional Commits specification during development, we can use handy tools or scripts to detect all changes since the last release and automatically increment the version appropriately. Conventional Commit messages could be:

fix: rounding error in final sum calculationfeat(invoices): add PDF exportchore: update dependencies

Their general form is

<type>[optional scope]: <description>

[optional body][optional footer(s)]While it can take some getting used to, it is certainly a good practice to conform to this specification for several reasons:

- It helps us during releases when determining versions changes.

- Other contributors or users gain a quick and concise overview of what changes are introduced.

- It forces committed changes to be in logical groups. If we cannot assign a distinct type or scope to the commit, the changes should be untangled, regrouped, and commited separately.

While learning and adopting the specification, one can certainly keep a cheatsheet nearby and take a moment to craft fitting commit messages. While the specification at conventionalcommits.org strictly formalizes the message structure, there is still flexibility in what types or scopes are available, and there is room for personal style and preference in how the description is phrased.

All in all, Conventional Commits, in combination with SemVer, nicely defines how changes are recorded and reflected to the outside, whether for dependency management, administration, or troubleshooting. Team members, users, and stakeholders will certainly appreciate this system over an opaque, and at worst contradicatory, versioning policy. But how do we communicate the changes in each version to our users?

Keeping a Changelog

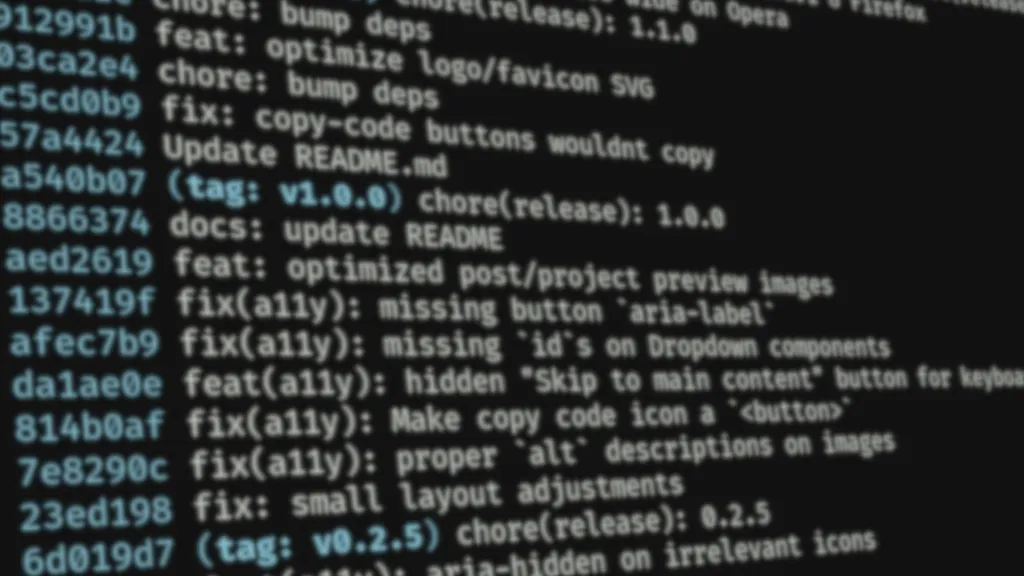

The obvious answer is a Changelog, a file where we add a list of new changes after each new release. This can be a lot of repetitive work when done manually, but fortunately, we can automate this as well, provided we adhered to the Conventional Commits specification during development! Our commit history might look like this:

bb84b39 fix: rounding error in final sum calculationfab74b2 feat(invoices): add PDF export6e241ca chore: update dependencies7e2c06a (tag: v1.2.3) chore(release): 1.2.3Our last release was 1.2.3. We made three changes and are now ready to do a new relase. Regardless of the specific tool, most of them will generate a new changelog entry for us that will look somewhat like this:

## 1.3.0 (2024-11-29)

### Features

* **invoices:** add PDF export (fab74b2)

### Bug Fixes

* rounding error in final sum calculation (bb84b39)Note that the new version will be 1.3.0 because a new feature was added, which calls for a minor increment. The level of detail, format, and the commit types listed can most often be configured for the specific tool used.

In any case, when we craft a new release, the changelog document gets a new section with new changes added to it, and any interested user can, for example, consult the changelog after updating to get a quick overview of what changed.

Using SemVer is especially useful here: if only the patch number changed, the user might just update the software without concern; however, if the major changed, the cautious user will first read the changelog to check if they can update without problems or if there are breaking changes relevant to his use case.

Useful tooling

As mentioned multiple times before, we want to automate our release processes. We are thus looking for tools to:

- Detect the last released version

- Parse all (conventional) commit messages since then

- Calculate the new version (according to SemVer)

- (Bump the version, for instance in

package.json) - Generate a changelog for the new release

Depending on your stack and setup, there might be different tools to consider; however, for Node.js projects, for example, there are plenty options, including:

- release-please creates release PRs

- commit-and-tag-version bumps version and generates changelog

- semantic-release handles the whole package publishing workflow

Although not necessary, there is also the option of integrating a commit linter, such as commitlint. The linter scans the commit message on commit, checks if it adheres to our Conventional Commits format, and aborts the commit if it does not.

With that, we can prevent the commit of faulty or insufficiently formatted messages. This might be overkill, but it can also be very helpful in teams to enforce good habits and ensure that no commits go undetected by our toolchain due to formatting errors.

The Recipe: summary

Having covered all the puzzle pieces for a good versioning workflow, let’s recapitulate and outline all the necessary steps:

-

When we commit changes to the code, we follow the Conventional Commits specification to craft well-typed and formatted messages describing the changes.

- 🤖 (We integrate a commit linter into the project, preventing malformed commits)

-

To release a new version, we review the commit types (

feat,fix,refactor, …) and calculate the new version number according to SemVer -

We then add a short list or summary of the relevant changes to our changelog

- 🤖 (Or we use a tool that bumps the version and generates the changelog)

Of course, there are plenty of scenarios where additional or different requirements, steps, and tools need to be involved in the release process. It is not mandatory to follow the listed conventions, but a growing number of open-source projects do adhere to them, and if in doubt, you should definitely consider adopting these practices for your project or team!